Part I: The Afro-Cuban Era

Salsa became known as an umbrella-term to represent the Afro-Cuban rhythms and dances popular in New York which have their roots in Africa and Cuba.

Afro-Cuban music made its way to New York during the first half of the 1900’s in-part by Desi Arnaz – a musician and actor famous in American television, and by Xavier Cugat – a musician from Spain who spent his early years training in Cuba – and after relocating to New York – became the bandleader of the resident-orchestra at the Waldorf-Astoria before and after World War II.

By 1945, the Palladium Ballroom opened its doors to those Afro-Cuban rhythms and became known as the Home of the Mambo.

All of this happened way before the era of Johnny Pacheco and Fania. Many ‘salseros’ wholeheartedly believe that the history of Afro-Cuban music (called Salsa, today) started with Johnny Pacheco, Hector Lavoe and Fania Records. That is only half the story.

Initially, the term Salsa grew to include rhythms specifically from Afro-Cuban origins: Son, Mambo, Son-Montuno, Guajira, Bolero, Guaguancó, and other Afro-Cuban rhythms along with their dances. But when Bugalú, Jazz, and Pachanga came to gain popularity – the term Salsa was expanded to include the modifications these rhythms underwent – popularized in New York and extending out across the US, Latin-America, the Caribbean, and Africa.

The rapid growth of this movement occurred towards the end of the 1960’s with Johnny Pacheco using Fania Records featuring Hector Lavoe, Willie Colón, Celia Cruz, Pete El Conde, Hector Casanova, and the likes, to usher it into the mainstream worldwide.

For many dance-studios in present day, the term Salsa may include Bachata and Kizomba. This article aims to fill in the blanks.

Benny Moré / Afro-Cuban Legendary Bandleader, Vocalist, and Arranger

Benny Moré / Afro-Cuban Legendary Bandleader, Vocalist, and Arranger

A Brief Overview of 1888 to 1923

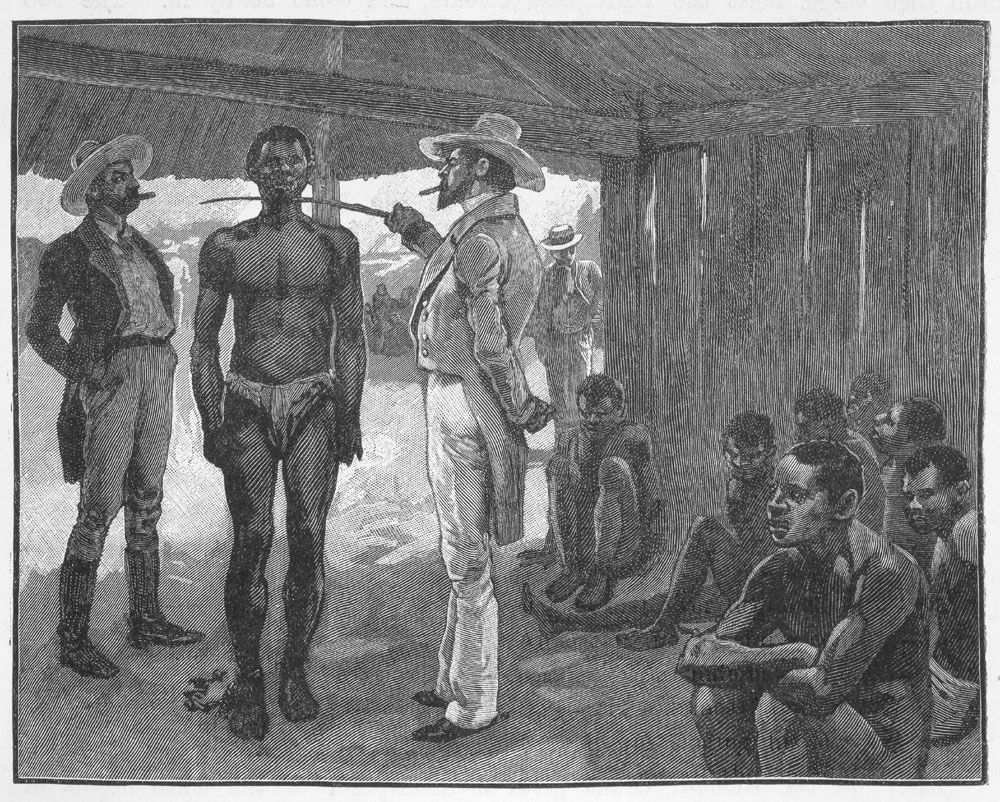

Buying Slaves, Havana, Cuba, 1837 (Franz Von Hierf)

Buying Slaves, Havana, Cuba, 1837 (Franz Von Hierf)

Slavery and racism were legal and regularly practiced in the major cities of Cuba and across the Caribbean. However, not every African, or black native, or minority was a slave; many lived free in rural areas – working, procreating, and celebrating, according to the norms of their own cultures and tribes.

The slave-trade from the late 1400’s to the late 1800’s caused that cultures and religious practices from individual tribes from within Africa were transplanted to Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Jamaica, and other lands in the Caribbean and Latin-America.

Forced labor and enclosed living quarters forced slaves to interact and mingle, leading to musicians and dancers among them to be exposed to the many various, polyrhythmic patterns; this merge gave birth to the first official Afro-Cuban rhythm: Rumba (which then evolved into a separate rhythm called Guaguancó).

Cuba outlawed slavery in 1888, which began the forced-desegregation of its education system through 1923. Undereducated blacks and other minorities were slowly integrated into schooling, mainly craftsmanship and music.

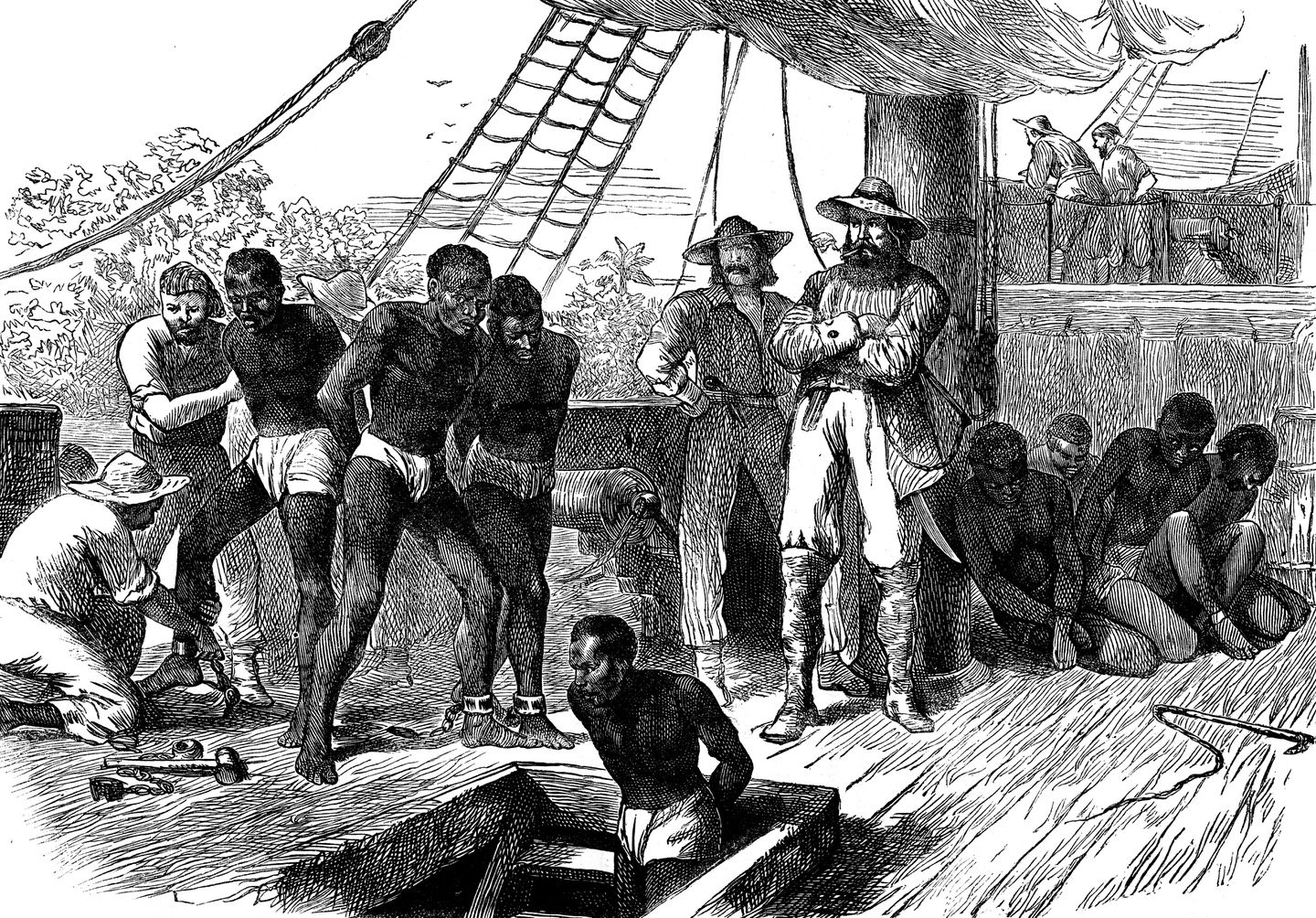

© Shutterstock/Morphart Creation

© Shutterstock/Morphart Creation

Out of this racial and musical mixture of European melodies and African-tribal/Afro-Cuban rhythms, came the development of rhythms and dances including Rumba, Guaguancó, and Bolero among others.

Listen to almost any song of Danzón or Bolero (two of the earliest Euro-Afro-Cuban rhythms), and hear the rich melodies of violin and flute (European influence) and the exciting tumbaos, or rhythms, of the percussion instruments and rhythmic grooves (African influence).

Rumba, Danzón, and Bolero

Rumba was officially formatted into a standardized rhythm in 1876 – consisting almost exclusively of percussion instruments; meaning – no melodic instruments.

As a dance, Rumba is strongly influenced by cultural and specific movements symbolic of some of the religions practiced at the time including Carabali, Orishas and Yoruba. A search on YouTube for Rumba de Cuba may help.

Danzón was created soon after, in 1878. Listening to a Danzón, one can clearly hear the European influences in the instrumentation, such as the European flutes and violins, followed by Afro-Cuban instrumentation.

For example, often the first half of a Danzón is accentuated by flute and violin – and the second half is dominated by a prominent bass syncopation with more percussion.

Israel ‘Cachao’ López / Afro-Cuban legendary bassist; pioneer of Mambo; songwriter; pianist / © Photo by Jakub Mosur March 5, 2005

Israel ‘Cachao’ López / Afro-Cuban legendary bassist; pioneer of Mambo; songwriter; pianist / © Photo by Jakub Mosur March 5, 2005

Among the most well-known pioneers of Danzón was Israel ‘Cachao’ López, although he was among many who popularized the rhythm, for example – his brother Orestes López, Antonio Arcaño, Arsenio Rodriguez, and popular orchestras including Sonora Matancera, and Orquesta de la Playa.

For a beautiful example of how lively and beautiful the Danzon rhythm can be, take a listen here with GOOD headphones or bass-speakers to this song called “Isora” – featuring Cachao on the contra-bass and Hollywood actor Andy Garcia on vocals, Alfredo Valdéz Jr on piano, among other talented musicians.

Bolero, as a rhythm and dance, had already been evolving – but finally had a more developed format by 1903, which quickly spread throughout Latin-America – particularly to Panamá; the construction of the Panama Canal was a vacuum for laborers from around the Caribbean, which caused that the musicians and dancers among them circulated the Bolero throughout the Caribbean, and North and Central and South America.

The Bolero’s distinct 1-3-4-5, 7-8-1 footwork dance steps aligned with the prominent bassline in the music, which essentially made it the only dance of this kind, at the time.

A modern example of Bolero, filmed very recently, helps to demonstrate the basic rhythm and footwork although remember that this is a modern example.

In the late 1920’s to mid-1930’s, the Son rhythm was still being developed, which gave new life to dancers and musicians. One of the hybrid rhythms born of this fusion is Bolero-Son; adding beat 2½ in the bass-syncopation is the primary modification of making a Bolero a Bolero-Son, as well as the chord-progression.

Son and Guajira, and the dance – Cha-Cha-Chá

Carlos Rafael Gonzalez et Marie Line au festivla Caribedanza

Carlos Rafael Gonzalez et Marie Line au festivla Caribedanza

The rhythm of Son became fully developed by 1923 – introducing an emphasis of a distinct syncopation; the musical DNA of Son consisted primarily of first guitar, second guitar, contra-bass, and clave sticks. The Son rhythm introduced crucial changes into Afro-Cuban music; the new “and-beat syncopation” of the contra-bass introduced a whole new feel for the music which had not been heard or danced to before, which revolutionized popular Afro-Cuban music of the time.

Take a listen with bass-headphones or speakers to this Son by “El Rayo” by La Nova Tradicional, and to this Bolero-Son by “Lágrimas Negras” by Celina Gonzales – and you will hear the unique bass-syncopation on the 2½ and 6½, which is what the Son introduced as standard for almost all Afro-Cuban songs from then until now.

The smooth, fluid sound of Son inspired the dance, by the same name. An example of Son performance could be valuable to see although it is important to note that dancing Son as a demonstration or performance is not the same as dancing Son, socially. Son has traditionally been dancing with a sidestep and with the timing of the steps accentuating the prominent accents of the bass on beats 4 and 8, which was a new concept, at the time, yet remains a standard form of dancing Son, today.

Guajira is the musical rhythm – but the dance is Cha-Cha-Chá most-often associated with this slow, smooth rhythm (however, please note that Cha-Cha-Chá is danced to six different Afro-Cuban rhythms including the Guajira rhythm).

The roots of Guajira date back to 1891 originally as a rhythm with 3/4 timing closely aligned with the Waltz, however it started undergoing modification to standard 4/4 timing in 1904 as an evolved alternative to the Bolero and Danzón.

Take a listen with bass-headphones to the most famous Guajira of all-time titled “Guantanamera” by Joséito Fernández, and to “Que Rico Bacilon” by Orquesta Aragón de Cuba, then to a beautiful, original Guajira called “Guajira Clásica” by Israel Cachao López, and a sweet, modern Guajira called “Guajira De Un Abandonado” by Calambuco.

And take a listen here to a gorgeous Guajira-Son titled “Vale Más” and to the precious Guajira titled “Verás” – both arrangements by La Época (featuring Palladium-era legendary bassist Alfonso Panamá and his daughter Raquel-María on vocals.

Raquel-María / Vocalist of “Vale Más” (Guajira-Son)

Raquel-María / Vocalist of “Vale Más” (Guajira-Son)

Adolfo Indacochea & Tania Cannarsa / Professional choreographers

Adolfo Indacochea & Tania Cannarsa / Professional choreographers

Cha-Cha-Chá, for professional dancers, is an opportunity to be extra-clear with finesse, fluidity, self-expression, and technique. According to professional choreographer Frankie Martinez, the slower tempo presents a greater challenge to many dancers because of the obvious fact that without heightened skills in dance-technique and self-expression, they will be less-impressive (Interview, Part II La Época, 2011).

Adolfo Indacochea noted, in a 2012 interview, that dancers of today would benefit greatly from a greater understanding of the Afro-Cuban rhythms played at all the socials at Salsa festivals and in class in dance-studios, around the world (Interview, Part II Re-Edited La Época, 2013).

Benny Moré / Afro-Cuban Legendary Bandleader, Vocalist, and Arranger

Benny Moré / Afro-Cuban Legendary Bandleader, Vocalist, and Arranger