Part IV: The Fania Era

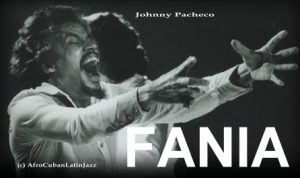

Johnny Pacheco / © AfroCubaLatinJazz

The Palladium Ballroom, located on 53rd and Broadway in the center of Manhattan, closed in 1966. The Palladium era was over; the Mambo craze was over, due to the overwhelming rush of social changes in politics, music and entertainment, and civil rights for Latinos, blacks, and women.

A new era was already brewing – Fania.

The Fania-era, from the mid 60’s to 1982, is a monster era to cover because of the size and scope of what Fania did for Afro-Cuban rhythms, for Latinos, for salseros everywhere in the world – for dancers.

To many, Salsa begins with Fania – a record-label which, from the mid-late 1960’s, broke sales records and whose musicians took the world by storm – spreading their own musical interpretations of Afro-Cuban rhythms.

To many others, Salsa begins in Cuba and is founded upon the many great musicians who invented and developed these rhythms in Cuba – and it equally includes the enormous contributions of the Fania musicians.

The term Salsa is an umbrella-term for the Afro-Cuban rhythms and dances that became popular in Cuba between the end of the 1800’s to the the mid 1950’s, and in New York City from the around 1945 to 1972 – and spread to the rest of the world.

This article picks up where the previous article left off – mid 60’s / early 70’s; Bugalú, Pachanga, and Cha-Cha-Chá were in – and the Mambo craze was on its way out.

Before we get into who the great musicians of Fania were, there is important ground to cover, first, for example, how Fania was founded, the controversy of Fania, and how Rock ‘N Roll and Funk (and Studio 54) effected the sound which Fania produced.

Fania cover / © LIC 84944b

The Founding of Fania

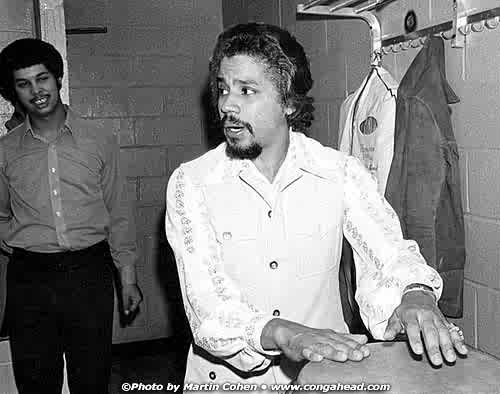

Johnny Pacheco / © Martin Cohen (CongaHead)

Dominican-born Johnny Pacheco teamed up with Jerry Massucci – and created, perhaps, the most powerful music record-label of Latin music, of that time: Fania Records.

Pacheco originally played bongos before specializing in the flute; during the late 1950’s, he played with many of New York’s top orchestras – and also traveled to Cuba, where he learned Afro-Cuban from some of the legendary musicians there. Pacheco is a multiple award-winning master-musician.

Massucci served in the US Navy stationed at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and later served in the New York City Police Department while earning degrees in Business Administration (graduating with honors) and later – a Doctor of Law degree. After resigning from the police department, he went to Cuba again under an employment contract as the Assistant Director of Public Relations, for the Department of Tourism.

In Cuba, in the early 1960’s, is where the paths of Pacheco and Massucci crossed – sharing a passion for Afro-Cuban music – and feeling that more of the world should be hearing the music and on a grander scale.

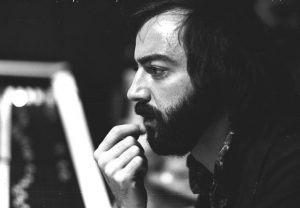

Jerry Masucci / © LIC 84944m

In 1964, Pacheco and Masucci founded Fania with the concept of signing mostly unknown musicians – because unknown musicians were much more affordable than the grand stars of the day. They sold their records out of the trunks of their cars in the streets of Spanish Harlem and the Lower East Side in Manhattan, and all over Brooklyn, the Bronx, Yonkers, and Queens – the heavily populated communities of Puerto Ricans and Dominicans.

By 1967, they were the fastest-growing music startup company; their music was becoming well-known across New York. By 1985, Fania had bought out competing Latin record-labels, and Fania’s musicians won dozens of Latin Grammies – again and again.

The Big Controversial Question:

Why Some Musicians Said No?

Tito Puente and Machito / © LIC 84987

Tito Puente and Machito / © LIC 84987

The most-commonly asked question about Fania is this: if Fania was so big, competitive, and popular, then why weren’t the stars of the Palladium – part of Fania?

This question pertains to the obviousness of the fact that some musicians were not part of Fania, which defies the urge to believe that they should have been.

Why didn’t some of the giants of Afro-Cuban music join Fania?

Why didn’t those geniuses from Cuba, such as Machito, Mario Bauzá, Arsenio Rodriguez, Cachao – or the masters from Puerto Rico, such as Tito Puente, the Palmieri brothers – Charlie and Eddie, Tito Rodriguez, Ismael Rivera and Rafael Cortijo – or the frequent legendary collaborators such Cándido Camero, Alfonso Panamá, Vincentigo Valdés, Bebo Valdés, Marcelino Guerra, and more – why didn’t they join Fania?

Some of them were key pioneers of Afro-Cuban music – the engineers of the rhythms who laid the foundation for Fania’s musicians to stand upon.

What happened?

Pérez Prado / © National Records Library

Pérez Prado / © National Records Library

The first main reason as to why many of the Palladium-era greats refused to join Fania was due to the feud between musical genius Arsenio Rodriguez versus Johnny Pacheco (mentioned in the Palladium Era).

Many musicians were loyal to Rodriguez – the inventor, innovator, and composer of many of the musical concepts and rhythms which Fania idolized and based their success on. Nearly a dozen musicians interviewed for the documentaries Part I and Part II of La Época – spoke emphatically of the Rodriguez/Pacheco feud.

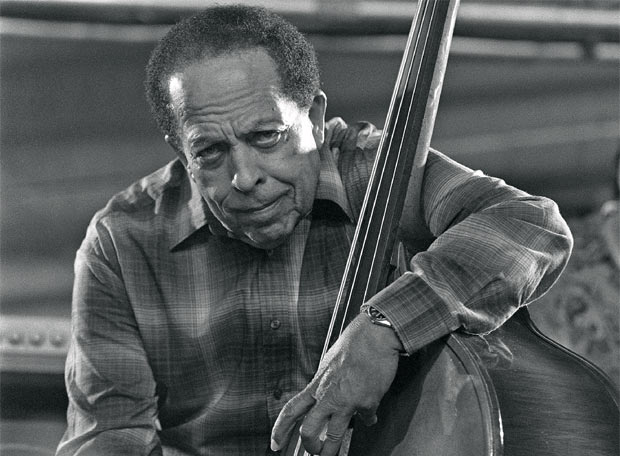

For example, considered among the very top-of-the-top bass-players of Afro-Cuban bass tumbaos, in New York, were Cachao López, Alfonso Panamá, and Cuajarón – yet not one of them joined Fania; each also happened to be regulars of Rodriguez’s conjunto.

What about Tito Puente? He was a musical genius; he and Pacheco collaborated often, before and after Fania, yet Puente refused to be part of Fania.

Many, many salseros of today mistakenly believe that Puente was a member of Fania; so very often, many cite albums of Tito Puente released in the late 70’s and 8o’s under the Fania label as evidence. However, the reason for this misconception is because in 1974, Fania acquired Tico Records – and quickly re-released songs in the Tico catalog (Tico Records was a major record-labels of the time to which Puente, Celia Cruz, Arsenio Rodriguez, and Joe Cuba, among other orchestras, were signed).

Mario Jursich Durán – founding member and ex-director of El Malpensante, wrote in “El Oído Del Ciego,” quoting Johnny Pacheco as saying, “Arsenio and his musicians were great people and they showed me so much, because the best school to learn Son was by learning from Arsenio himself”.

Israel “Cachao” López / / © LIC 84966CL

Israel “Cachao” López / / © LIC 84966CL

The second main reason was, simply put: those musical geniuses and pioneers of Afro-Cuban rhythms had a very different concept of Afro-Cuban music than the concept of Johnny Pacheco (musical director of Fania) and Jerry Masucci – the Fania co-creators.

Fania’s music is amazing! Pacheco is a master-musician – with nine Grammy nominations and the Latin Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. Yet, he had a very different concept of how Afro-Cuban rhythms ought to be played, heard, and experienced; it was not better or worse – but it was different.

This brings us back to why some of the greats refused to join. For example, many ask why Celia Cruz, who was Cuban, decided to join Fania – especially since most of her Cuban contemporaries refused to join.

The answer is quite simple: Cruz officially joined Fania in 1974 – only well after the passing of Arsenio Rodriguez; she could have joined earlier but did not. In addition to this, Pacheco made her an attractive offer to end her contract with Sonora Matancera which of course led to her ending her contract with Tico Records – the record-label he ended up acquiring the same year; her decision was obviously the correct one.

Many other iconic musicians declined to join Fania: bandleader Pérez Prado – known as the “King of the Mambo”, piano virtuosos Bebo Valdés and his son Chucho Valdés, pianist and composer Facundo Rivero, master-percussionists Patato Valdés and Mongo Santamaría, vocalists Miguelito Valdés, Marcelino Guerra and Vincentigo Valdés – all Cuban, all declined to join Fania.

What about one of the largest and most successful orchestras – El Gran Combo – why didn’t they ever join Fania?

The 1970’s – Rock ‘N Roll, Disco, Funk, R&B

Hippies, Sexual Freedom, and Drugs

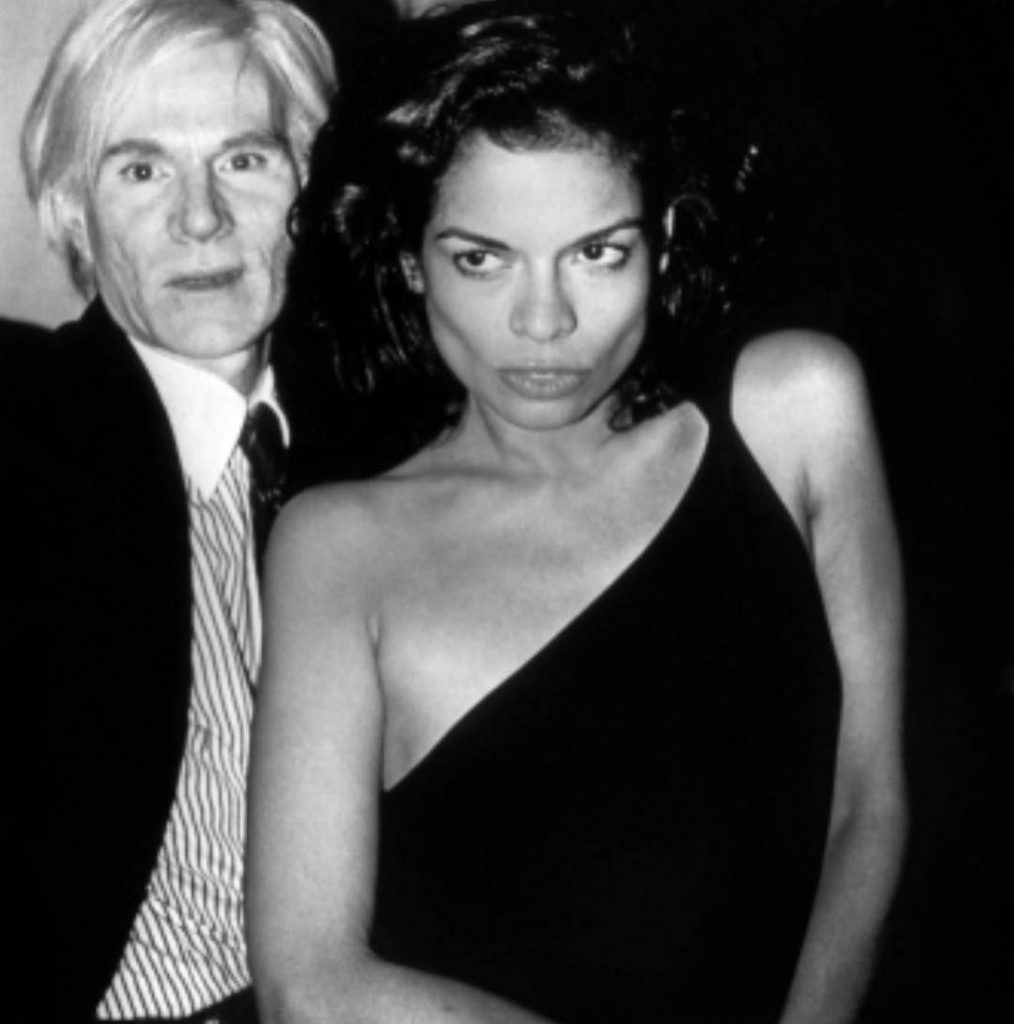

Bianca Jagger & Andy Warhol @ Studio 54 / © LIC 84981BJ

Bianca Jagger & Andy Warhol @ Studio 54 / © LIC 84981BJ

Highly probable is that perhaps most adults and teenagers, in and around New York during the mid 1970’s, heard about Studio 54 – the default, go-to, must-be-at night club for A-list rockers, such as David Bowie, Mick Jagger, and Freddie Mercury.

At a time when Fania was dominating the Latin scene – a concert in Yankee Stadium in 1973 in front of more than 40,000 people, a concert in Zaire, Africa alongside Funk-legend James Brown, attended by more than 80,000 people, and other large concerts in Panama and Puerto Rico – musical genres were being fused; Latin musicians were branching out into other genres of music.

With this fusion came an entirely new crowd – rockers, hippies, and freestylers. It wasn’t just the Cheetah Nightclub or Corso’s Nightclub in New York City that was where dancers were gathering, but now salseros, of the time, were being exposed to other genres – and many of them who also liked Rock – were gathering at Studio 54.

Freddie Mercury & Brian May / © LIC 84974FMQ

Freddie Mercury & Brian May / © LIC 84974FMQ

Some of Fania’s star musicians were also frequent collaborators of bands of other genres, such as Rock ‘N Roll, Funk, Disco, Jazz, and R&B.

Afro-Cuban drum rhythms, or Latin beats, were finding their way across genres, for example, “You Should Be Dancing” was a Disco hit from the Bee Gee’s as well as “Turn the Beat Around” from Vicki Sue Robinson.

Among the more recent and familiar examples are Michael Jackson’s “Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough” with the congas, maracas, and the glass bottle tapping a variation of the clave-pattern, and “These Are the Days of Our Lives” from Queen, the video of which opens up with the three congas front-and-center (though this came years later).

Jorge Santana, brother of famed Carlos Santana – both gifted guitarists, fused electric-guitar into Fania’s interpretations of Afro-Cuban music – providing a unique feel of Funk – such as in this song “El Ratón” with Cheo Feliciano and the Fania All-stars – filmed at Madison Square Garden, in New York City in 1974.

Bianca Jagger @ Studio 54 / © LIC 84981BJa

Fania grew so big, that in 1968, Pacheco masterminded an orchestra of Fania musicians called Fania All-Stars, which he promoted as the top-of-the-line Fania musicians; Fania All-stars became more famous than the label itself.

Fania reigned from 1968 to the mid 1980’s; it dominated the Latin music market and radios.

The highly competitive nature of Fania’s marketing strategy as well as the aggressive nature of the business dealings, many of which cheated most of the musicians out of royalties and fair fees, contributed to their worldwide success and the global passion for Salsa music and dancing.

Willie Colón and Héctor Lavoe – Giants of Fania

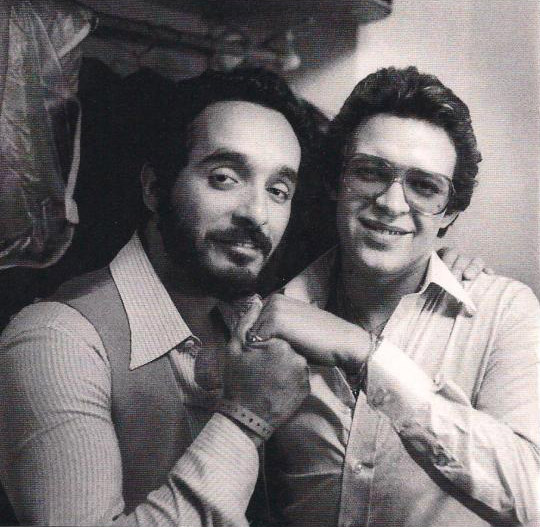

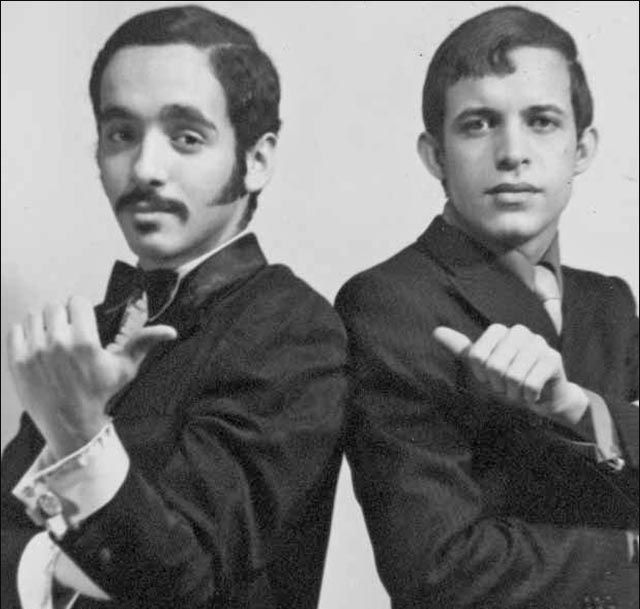

Willie Colón & Héctor Lavoe / © LIC 84944-WCHL

Willie Colón & Héctor Lavoe / © LIC 84944-WCHL

In 1967, two of the most influential musical figures of Fania were signed to the label – Willie Colón and Héctor Lavoe.

Remember, the Palladium Ballroom had closed a year earlier – and Latino families, especially, were still frequenting dance-clubs and buying up Latin records across New York.

Also remember, the great bandleaders of Afro-Cuban music were still performing concerts and recording albums – and the music of Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and James Brown was hugely popular; musicians were being influenced by many new social developments and musical developments, of the time.

This was a time when music and dancing, and drugs, violence, and sexual exploration were becoming a way of life, for many.

Colón, born in New York in 1950 to Puerto Rican parents, began playing trumpet and trombone in the underground night-clubs of New York in his early adolescence from 1964 at the height of the Bugalú, Pachanga, Cha-Cha-Chá – the last years of the Palladium where the generation of pioneers before him were still playing for sold-out concerts. In 1967, at sixteen, he was signed to Fania – as a trombonist, but later became a vocalist and songwriter.

Lavoe, born in Puerto Rico in 1946, he first learned saxophone but then developed an enormous talent for singing – he went on to practice crystal clear diction, etiquette, and stage-presentation. At age seventeen – in 1963, his father sent him to live in New York City, and in 1965, he began recording – singing Boleros for a local band.

In 1967, through co-founder and musical director of Fania, Lavoe met bandleader and trombonist Willie Colon resulting in Lavoe records vocals on the entirety of Colón’s first album titled “El Malo”.

Colón and Lavoe knew the streets and the needs of the people to escape the chaos and social pressures of the times; they provided the Salsa world with styles, sounds, and energy from the streets. Among their most beloved arrangement together are the popular “Que Lío” and “El Cantante”.

They became giants! Their musical collaboration lasted more than seven years and resulted in ten albums of a new sound unheard before: Colón blasted the trombone in the exciting mambo sections of their arrangements, and Lavoe led with his strong vocals and passionate lyrics.

Perhaps, the most widely circulated images of the duo, come from their performances of their unique hit-song “Guajira Ven” with Héctor Lavoe -center, Willie Colón – right, and the great bongocero José Mangual – left. The song begins as a Guaracha rhythm, then in the more uptempo section (montuno section), it becomes a Son-Montuno rhythm.

Willie Colón & Héctor Lavoe / © LIC 84944-WCHL2

In 1973, Lavoe went solo – where his fame continued to grow.

Among the members of their original Willie Colón orchestra was José Mangual, Jr, a bongo-player, who said in an interview in the original release of the award-winning documentary-film about the History of Afro-Cuban music and Salsa from Cuba to New York – Part I La Época – The Palladium Era, that those times were very alive, exciting, and that the success was faster than anyone had ever expected.

Colón became involved in politics and law during recent years, and has won countless awards including the Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award from the Latin Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences.

Sadly, Lavoe lost his life in June of 1993 due to complications of AIDS. From early in his career, he became heavily addicted to drugs. Though, he successfully recovered from his alcohol and drug addiction after completing rehabilitation and therapy, he suffered deeply, emotionally, which was further impacted by consecutive losses: the deaths of his father and son, the destruction of his apartment in a fire, and other immensely saddening turmoil.

Seven Albums with the great Pete “El Conde” Rodriguez!!

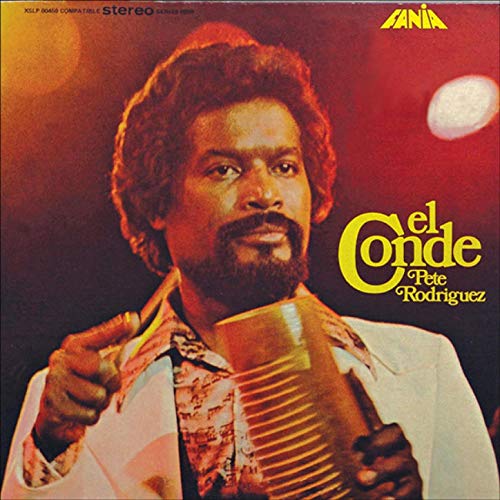

Pete “El Conde” Rodriguez / © LIC 84941-PECR1

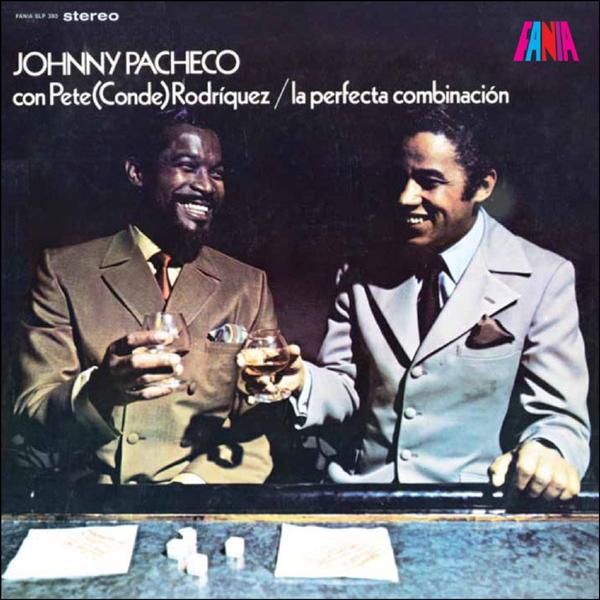

One of the very first musicians to be signed to the Fania label was a gifted percussionist (bongos and congas) and excellent vocalist with a unique precision and clarity – Pete “El Conde” Rodriguez.

Born in 1933, he was born and raised in Puerto Rico, where he received his foundations in music by his father. In 1947 – at age thirteen, he was relocated to New York City, where while attending school, he continued developing musically.

During Rodriguez’s early musical years, he focused his studies on Afro-Cuban rhythms; his father was well-versed – which is what led to Rodriguez himself to become known among his peers as an expert in Afro-Cuban rhythms such as the Son, Bolero, Guaguancó, Montuno, and Bugalú.

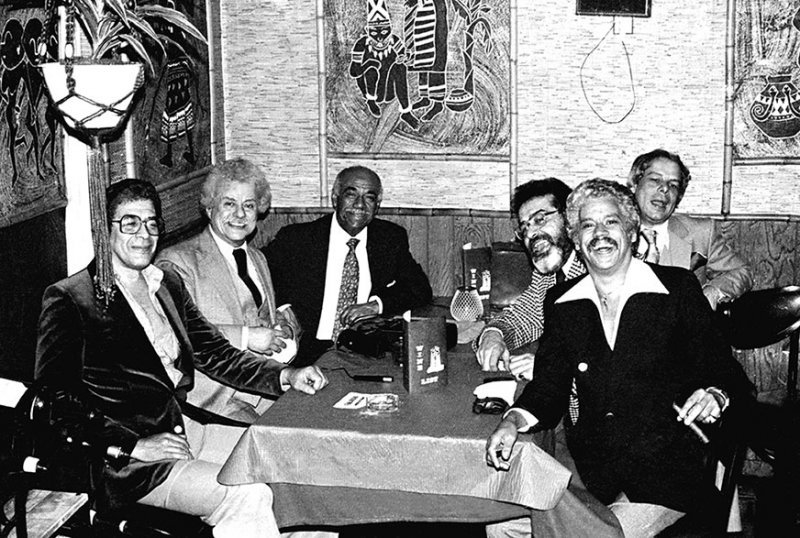

Pete “El Conde” Rodriguez & Johnny Pacheco / © LIC 84941-PECR3

From 1953 to 1956, he served in the US Air Force and fought in the Korea War where he endured dehumanizing racism and severe emotional abuse and discrimination at the hands of his superiors – an experience which shaped his personality and life. Rodriguez was known among his peers as the rarest of gentlemen – one of character, humility, and great integrity; he shared with those closest to him that his experiences in the military taught him that among the most important virtues in life was the virtue of humility.

In 1963, after returning to New York and developing himself musically, he was discovered by Johnny Pacheco – and they recorded an album titled “Suavito.” A year later, after Pacheco co-founded Fania, Rodriguez reunited with him – and they released seven albums over the following nine years to enormous success from New York, Africa, and South America. Among their many hits, are the smooth Son-Montuno titled “Sonero” and the Son titled “Catalina La O”.

Pete “El Conde” Rodriguez / © LIC 84941-PECR2

Despite Rodriguez’s great respect for the many Cuban legends who refused to join Fania, due to their protest of what they considered was a betrayal of the roots of the music, Rodriguez became involved in what is considered, perhaps, the biggest controversy of Rodriguez’s career.

In their hit song titled “La Esencia del Guaguancó”, Rodriguez sings the verse, “Con Pacheco, no hay quien pueda – es el rey del Guaguancó” which in English says, “With Pacheco, no one can compare – he is the king of the Guaguancó” which was a sneaky jab that Pacheco took at the inventor of the most popular form of the Guaguancó rhythm called Guaguancó Solar (at the height of one of the biggest feuds during the Palladium era which was between Cuban legend Arsenio Rodriguez and Dominican bandleader Johnny Pacheco).

In 1974, Pete El Conde went solo – to award-winning success. Then, between 1983 and 1989, Pacheco and Pete El Conde reunited – and released four more albums – one of which was nominated for a Latin Grammy award.

During his distinguished career, Rodriguez worked with other legendary bandleaders including Tito Puente and the Palmieri brothers – Charlie and Eddie. In 2000 – the same in which Tito Puente passed away, Rodriguez suffered a heart-attack and died after refusing to undergo heart surgery; he was 67.

Larger Than Life Was the Amazing Celia Cruz!!!!

Celia Cruz / © LIC 84966CLCZ1

Born in Havana in 1925, Celia Cruz was the eldest of fourteen siblings. While studying to be a literature teacher, she began to perform with local bands at cabarets and dance-venues and competing in radio contests – almost always winning top place. By 1947 – at age 22, she began studying music-theory and voice after learning that she could earn, in a single day, as much as teachers do in a month.

According to Cuban trumpeter Agustín Caraballoso (Part I La Época, documentary), while arriving with Beny Moré (legendary Cuban vocalist) for a concert in the later part of 1947, they observed Celia Cruz singing and performing her last two songs on stage. Moré and Caraballoso were so impressed, that they invited her to stay an extra hour – and join them for their first two numbers, which she did to great reception.

Word spread around Havana and other cities in Cuba, and eventually reached the great bandleader Arsenio Rodriguez, who invited Cruz to join his conjunto for various performances. Her popularity sky-rocketed while performing with Rodriguez.

By 1950, Rodriguez had already made several trips to New York in hopes of restoring his sight (as musicians had been urging him to do). Cruz continued with his orchestra, led by feature trumpeter Felix Chappotín, while Rodriguez was away.

In New York, Rodriguez reconnected with the contemporaries he used to work with in Cuba, such as his dear friend Miguelito Valdés (former vocalist of Orquesta Casino de la Playa which recorded five of Arsenio’s compositions – making them hits), Machito and Mario Bauzá, who were popularizing his rhythms and songs; they encouraged and finally succeeded in convincing Rodriguez that he should relocate to New York.

Tito Puente and Celia Cruz — © Jack Vartoogian, Getty Images

Upon returning for what became his last trip back to Cuba (before permanently relocating to New York), the lead vocalist for the band Sonora Matancera, named Myrta Silva, decided to go back to her native Puerto Rico – and it was Rodriguez who persuaded the leader of that band to give the lead vocalist position to Cruz, citing that the songs Sonora Matancera released could be sung by a female vocalist while his own songs were more ideal for a male voice.

Cruz became a star in Cuba, Mexico and across Latin-America, and in the US; she stayed with Sonora Matancera for fifteen years during which she recorded over 180 songs, including hits “El Yerbero Moderno” and “Mata Siguaraya”, which her old friend Cuban great Beny Moré also popularized as a Bolero-Son, and which many years later – superstar Venezuelan bandleader Oscar D’León famously performed on stage at one of his performances – giving credit to Moré.

In 1960, the orchestra moved to Mexico, and after several years of romance with the orchestra’s second trumpeter, Pedro Knight, they finally married, and bought a home in New York, in 1962. Pedro then exited the orchestra to concentrate on his role as Cruz’s music manager (Dominican-born musician, nicknamed Chiripa, replaced Knight; Chiripa – the first non-Cuban to join the orchestra).

During her time in New York, Cruz met sang for most of the popular orchestras in New York, such as the Tito Puente Orchestra, the Machito and his Afro-Cubans Orchestra, Johnny Pacheco, and others.

Johnny Pacheco & Celia Cruz / © Izzy Sanabria

It was widely known that Pacheco was very secretive about his business dealings with musicians, as the co-founder of Fania Records – and was very aggressive in his pursuit of acquiring talent. Contrary to popular belief, however, it was because Pacheco considered Sonora Matancera as competition and wanted to remove as much as possible, that he offered Cruz a sizable contract to join his orchestra – effectively ending Sonora Matancera’s reign (according to several musicians interviewed for the award-winning Part I La Época).

However, in 1966, Tito Puente had already contracted her for an album together – instantly becoming an international success. Their hit-song “Bemba Colorá” became known as her signature hit (the original version begins as a Rumba rhythm and then becomes a Son-Montuno, but in most concerts in the US, it is performed only as a Son-Montuno). They ended up recording for four albums together.

Cruz’s contracts allowed her to perform concerts with Fania but not record any albums until her contract with Tito Puente (album and live concerts) ended.

Celia Cruz was one of the most famous musicians of the Fania era. Not only one of the most humble musicians one could ever meet, not only one of the most unique voices in “Salsa”, but she was also a very talented, natural dancer. She often performed in concerts with Tito Puente, with whom she maintained a close friendship and musical collaboration until her last years.

She passed away in July of 2003.

Rubén Blades – the “Intellectual of Salsa Music”

Ruben Blades / © Echoes, Getty Images

Having won nine Grammy Awards plus eight other nominations, plus five Latin Grammy Awards, it would be impossible to tell the story of Fania without mentioning songwriter and vocalist Rubén Blades.

Born in Panamá to a Cuban musician and actress and to a Colombian musician and US Federal agency worker, Blades got a job working in the mailroom of Fania just to get as close to the musicians as possible.

Ruben Blades & Willie Colón / © Michael Ochs, Getty Images

Blades released an album with Pete El Conde Rodriguez, then soon after began collaborating with the exceptionally skilled percussionist and solo artist from Puerto Rico named Ray Barretto, already signed to Fania, and with another exceptional musician, pianist, and solo artist of Jewish descent named Larry Harlow, who also already signed to Fania.

Not long after, Blades began yet another musical journey with Fania giant – trombonist and bandleader Willie Colón, with whom he recorded several albums.

In 1978, Blades composed what essentially became the signature song of Fania giant Hector Lavoe – titled “El Cantante” (in 2006, a biographical film of the same title, featuring Marc Anthony and Jennifer Lopez was released to huge success).

Easily, the most popular and beloved of his songs is “Pedro Navaja” (also seen here).

Rubén Blades / © LIC 84949RbBl

Also, in 1978, the Blades/Colón album titled “Siembra” sold over 25 million copies – making it the best-selling salsa record in history, at the time.

Blades is also a guitarist and an expert in Central American rhythms, included Cumbia. One of his most beloved compositions is titled “Eres Mi Canción.”

Unsurprisingly, to many musicians familiar with the aggressive nature and business dealings of Fania, Blades became discontent with the record company and tried unsuccessfully to terminate his recording contract, but was legally obliged to record several more albums.

In addition to his many achievements in music, Blades is a graduate of Harvard Law – having earned his Masters in International Law there, and is a accomplished actor and politician.

Larry Harlow, Ray Barretto, and Yomo Toro

Larry Harlow / © LIC 84974LH, AP

Larry Harlow, known as The Marvelous Jew, made over 250 albums in his lifetime – and is a major icon of the Fania label.

Harlow is a dedicated admirer of Arsenio Rodriguez, which is why many of the songs he composed and arranged have a unique feel – a more old-school and original feel to them – and some of his songs are actual re-arrangements of Arsenio’s song. After Rodriguez’s death, these re-arrangements became of particular important in the Salsa community – as Harlow continues to tour with his band – and is well-respected by organizers of Salsa festivals worldwide.

For example, “El Malecón” is a Son-Montuno with breaks which parallel the unique style of Arsenio Rodriguez. And, then there is one of Arsenio’s most beloved songs which has been re-arranged many times by orchestras over the years – titled “No Me Llores” – another Son-Montuno, which Harlow re-arranged beautifully; take a listen.

In addition, there’s yet another Son-Montuno by Arsenio Rodriguez titled “Suéltala” – the original is with Arsenio on tres and his brother QuiQui on tumbadora, his longtime orchestra-member Alfonso Panamá on bass executing very unique and challenging Afro-Cuban tumbaos which were not in Harlow’s re-arrangement, René Hernandez on piano, and with Julian Llanos, Santiago Cerón and Marcelino Guerra on vocals and chorus, and with Chocolate Armenteros, Vitín Paz and Agustín Caraballoso on trumpets; and take a listen here to Harlow’s great re-arrangement.

Tumba y Bongó is another popular song from Arsenio Rodriguez, which has been re-arranged by several orchestras, however take a listen here to Harlow’s re-arrangement, which is a Montuno rhythm.

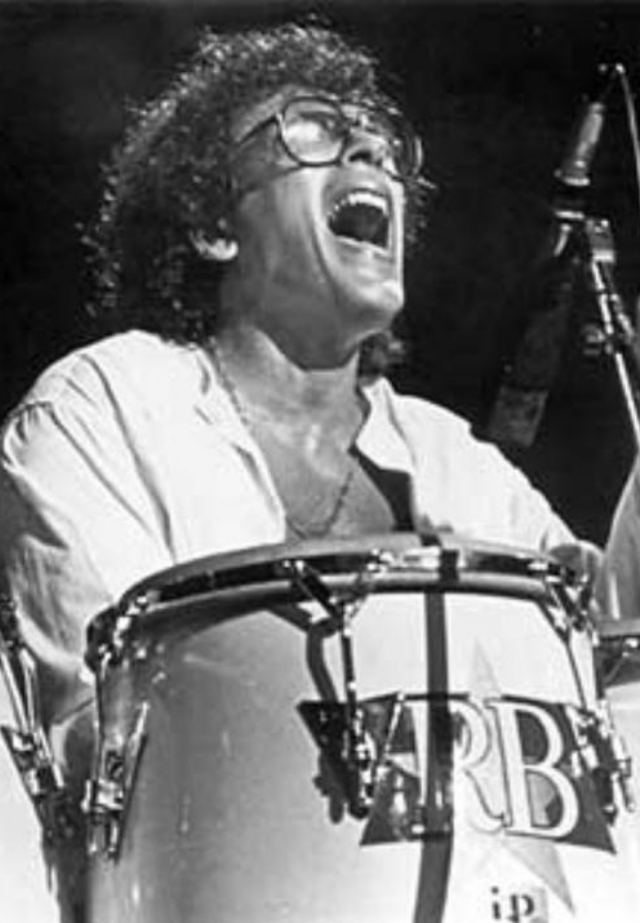

Ray Barretto / © LIC 84948RB

Ray Barretto was a longtime member of the Fania Records label – and an expert in Afro-Cuban tumbaos.

Under the record-label Tico Records, in 1962, his first hit was titled “El Watutsi” – a modified Son-Montuno in the form of Pachanga, and in 1965, he signed with United Artists Latino under which he released several albums featuring Bugalú.

By 1967, Barretto was a star performer in Afro-Cuban orchestras, Latin bands, and Jazz orchestras, including Tito Puente, José Curbelo, and Jazz giant Charlie Parker.

A star, he signed with Fania Records in 1967 and created more albums to rising success.

However, after the death of Arsenio Rodriguez, on 30 December 1970, a feud began among most of Barretto’s main musicians regarding the band’s direction.

Barretto was an admirer of Rodriguez , which is reflected in some of Barretto’s Afro-Cuban arrangements, however, there was a growing sentiment in his group that he was being too experimental with his tumbaos; the other members of his group wanted more of a typical Charanga style.

Unable to compromise, the majority of the members of his band abruptly abandoned Barretto – and formed Típica 73, an enormously success orchestra – with some of the members of this newly formed group eventually going on to become famous bandleaders and solo-artists themselves – among the most famous, today, are José “El Canario” Alberto, Adalberto Santiago, and superstar Cuban violinist Alfredo de la Fé.

Barretto turned to Jazz and Afro-Cuban Jazz although he remained one of Fania’s main musical directors. One of his greatest contributions, played often by deejays at Salsa festivals, is “Quítate La Mascará”.

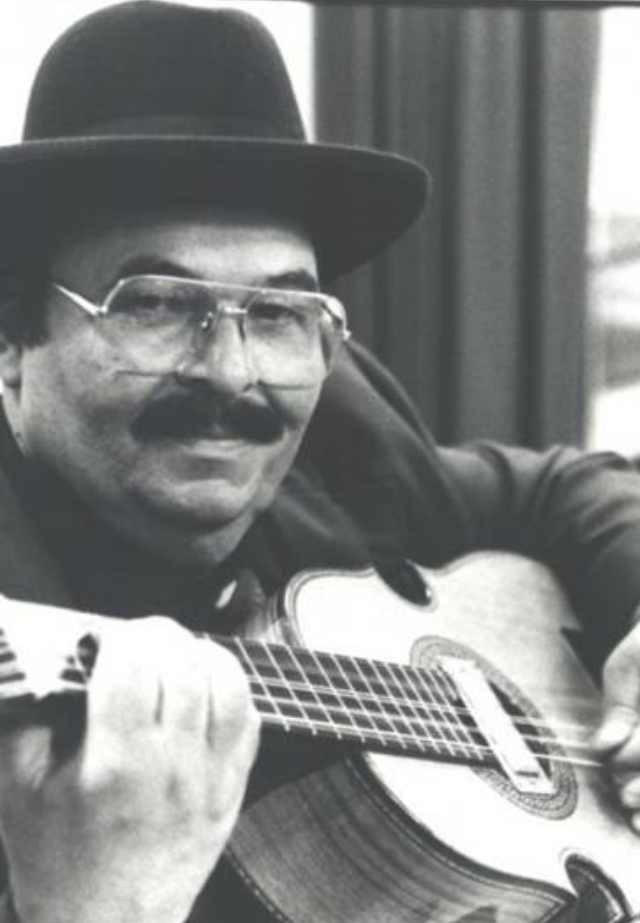

Yomo Toro / © LIC 84977YT

Without emulating the sound produced by Arsenio Rodriguez – with his tres guitar, there was going to be a void in Fania’s music.

By the late 1960s, that void was filled in Fania’s music primarily by two distinct musicians – Yomo Toro on the cuatro-guitar and by Charlie Rodriguez on the tres-guitar; both were from Puerto Rico – both openly spoke of being inspired by Arsenio.

Toro recorded and performed with the bands of Johnny Pacheco, Willie Colón, Héctor Lavoe and Rubén Blades, and collaborated with Tito Puente, with bassists Alfonso Panamá and Cachao López, as well as plenty of other super-talented musicians.

One of the most exciting tracks featuring Yomo Toro, Willie Colon, and Hector is “La Murga” – take a listen with good headphones and you will hear Yomo Toro taking a solo – and it is announced in the song. Also, in this track, you can hear the rarest of occasions when Willie Colón allowed a walking-bass in any of his tracks; a walking-bass was frowned upon by the majority of bands outside of Cuba because the melodic rhythm of the bass (called a “walking bass”) often proved to difficult for the other musicians to keep up, who instead preferred a standard Son-tumbao of 2½-4 & 2½-4 (for dancers, it’s 2½-4, 6½-8).

Another very popular track featuring Yomo Toro with Fania All-Stars is titled “Quitate Tú” — in which can be seen and heard Ray Barretto on congas, Pete “El Conde” Rodriguez and Johnny Pacheco on vocals, plus … well, take a listen and see who you recognize!!!

With good headphones or bass-speakers, take a listen to these two Son-Montunos titled “Ven Mi Mora” and “El Cachetero” – both by tres-player expert Charlie Rodriguez.

Cheo Feliciano and Roberto Roena

Cheo Feliciano / © Julieta Cervantes

Cheo Feliciano, born in Puerto Rico in 1935, played percussion and sang in local bands of other adolescents in the neighborhood until his parents moved the family to Spanish Harlem, in New York City, in 1952, where he developed himself musically by spending his free time with musicians.

Bandleader Tito Rodríguez took him into his band – performing at the Palladium and other major venues in New York, however, Feliciano eventually exited and instead joined the orchestras of Kako (who was a longtime member of the Arsenio Rodriguez Conjunto) and of Mon Rivera.

In 1955, Rodríguez joined the Joe Cuba Sextet, as a vocalist, and remained for twelve years to greater success – continuing to perform at the Palladium.

In 1967, he joined the Eddie Palmieri Orchestra, as a vocalist, over two years.

However, as did many musicians of the time, Feliciano began to use and abuse illegal drugs – nearly losing his life. Palmieri forced him out of his orchestra – and Feliciano returned to Puerto Rico – admitting himself into a rehabilitation center. Upon successful rehabilitation, Feliciano became a serious advocate against drugs – an anti-drug spokesperson, and volunteered in aiding other musicians who also struggled.

In 1971, Feliciano returned to music as a soloist – earning awards – and becoming noticed by Johnny Pacheco; he recorded fifteen albums under the Fania label until he exited in 1982.

Over the following thirty years, he continued performing – reuniting for concerts with Joe Cuba and Eddie Palmieri as well as Johnny Pacheco – with whom he remained close until the time of Felicianos’s death in 2014.

Roberto Roena / © LIC 84944RR

Roberto Roena was born in 1940, in Puerto Rico, and by age seven, was performing Mambo dance-choreographies in the local neighborhoods often winning contests – eventually earning a contract to perform weekly on a television program. Roena was also a gifted conguero.

Well-known bandleader and percussionist Rafael Cortijo was impressed – and began tutoring Roena in music – teaching him how to play the bongos and cowbell; by the age of 16, Roena was a member of the Cortijo y Su Combo orchestra – with famous lead-vocalist Ismael Rivera – touring Latin America, the United States, and Europe.

At a time of intense racial discrimination against musicians, the band’s success was unexpected and extremely rare.

Among the hits of Cortijo y Su Combo include the hit song “El Negro Bembón” and the exciting Son-Montuno (which many dancers today would prefer to refer to as a Pachanga) titled “Moliendo Cafe” (with Ismael Rivera singing in both).

In 1962, after returning from performing a concert in Panama, at the height of the orchestra’s success, the lead singer – Ismael Rivera, was arrested for drug possession – and spent more than three years in federal prison, which caused the orchestra to disband – and form what soon became (and still is) one of the most successful orchestras in the history of Puerto Rican / Afro-Cuban music (Salsa) – titled El Gran Combo.

Roena did not join the new orchestra in its conception, out of loyalty to Cortijo. However, after Cortijo relocated to New York to join its vibrant music scene, Roena then joined El Gran Combo, with which he stayed until 1969.

In 1969, Roena formed his own band – titled Roberto Roena y su Apollo Sound, which became known as one of the most popular Salsa bands, in Puerto Rico.

By 1973, Roena was an established member of Fania All Stars – having impressed Johnny Pacheco and other musicians under the Fania umbrella.

Today, Roena still tours – performing.

Barreto, Puente, Machito, Quijano, Palmieri and Pacheco

© 1980, Joe Conzo

Recently, in the Dominican Republic, was a concert tribute to Fania co-founder and master-musician Johnny Pacheco (who can be seen being seated in the chair while other sing in his honor wearing the white jacket and black slacks); they sing one of Pacheco’s signature songs “Quitate Tú”.

Some of the musicians are contemporary, however, you can notice Cheo Feliiciano, Roberto Roena, Bobby Valentin, Papo Lucca, Adalberto Santiago, Ismael Miranda – which reunited these Fania musicians, along with superstar salseros Oscar D’León and José “El Canario” Alberto; even Pacheco, himself, takes the mic and sings at the end.

At the same concert, here you can watch and hear Oscar D’Leon sing and lead the orchestra in a beautifully, smooth Son-Montuno titled “Sonero”, in honor of Pacheco (seated in the audience wearing the white jacket with the white hair). Take note that the tres-guitar is being played by Charlie Rodriguez (taking a short solo), who regrettably past away only in 2019, but was one of the main tres-guitarists who gave Pacheco’s Fania All-stars and the main bands under the Fania umbrella – the unique sound of the guitar.

There are many musicians of these times, who have not been given the spotlight here in this article, and it is worth listening to their contributions to “Salsa” (including La Sonora Ponceña by Papo Lucca Jr – one of the most gifted pianists of the Fania era) – but researching “Fania” online will provide a pool of the great music of Fania!